As Time Goes By

As Time Goes By A Little Learning

A Little Learning A Mother's Spirit

A Mother's Spirit Daughter of Mine

Daughter of Mine A Girl Can Dream

A Girl Can Dream A Strong Hand to Hold

A Strong Hand to Hold A Sister's Promise

A Sister's Promise To Have and to Hold

To Have and to Hold Pack Up Your Troubles

Pack Up Your Troubles Keep the Home Fires Burning

Keep the Home Fires Burning Another Man's Child

Another Man's Child The Child Left Behind

The Child Left Behind Mother’s Only Child

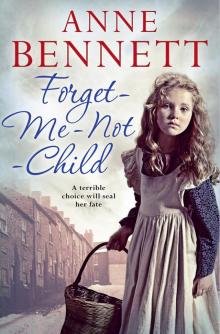

Mother’s Only Child Forget-Me-Not Child

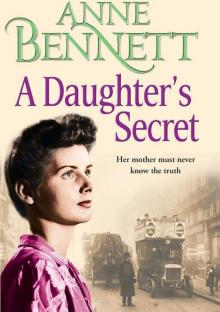

Forget-Me-Not Child A Daughter's Secret

A Daughter's Secret Walking Back to Happiness

Walking Back to Happiness Far From Home

Far From Home Till the Sun Shines Through

Till the Sun Shines Through